“Can’t keep living like this”; BC interior water quality problems coming to a boiling point

INTERIOR BC – Water is commonly regarded as British Columbia’s most precious resource, but it’s become nothing short of a source of stress for communities across the interior.

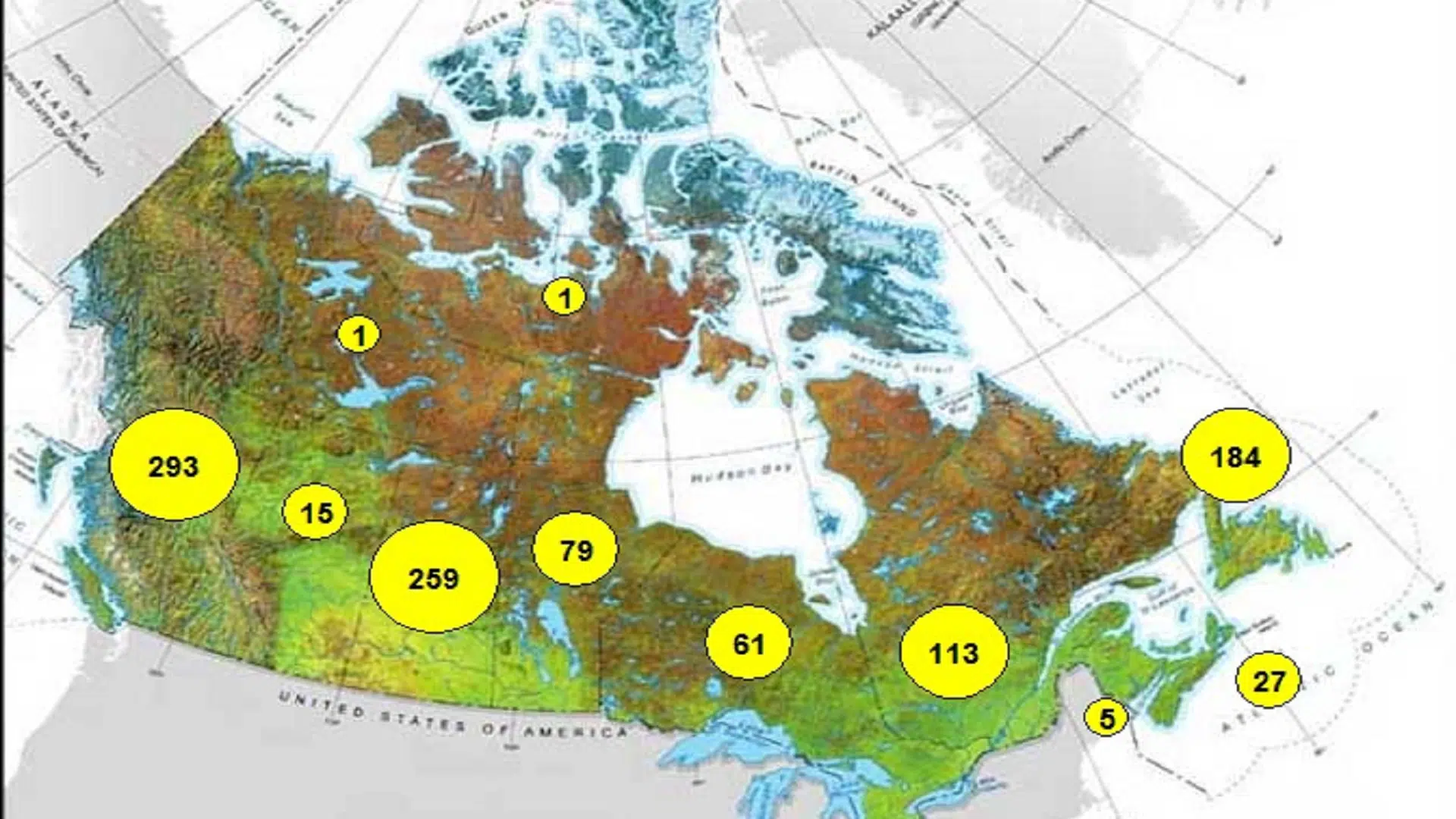

Interior Health is the authority that issues water advisories in the Kootenay, Okanagan, Thompson, Cariboo and Shuswap regions. According to its website, there are currently more than 290 total notices, including quality advisories, boil water notifications and do not consume orders, across those regions. This is due to a number of factors from inadequate water system operation to harmful parasites.

A group of residents from Sparwood’s Elk Valley Trailer Park brought part of the Kootenays’ water situation to Lethbridge News Now’s attention in early November.

BC’s water is regulated under the Drinking Water Protection Act that states under section 6(a), “a water supplier must provide, to the users served by its water supply system, drinking water from the water supply system that is potable.”