Behavioural analysis can help answer the ‘why’ in B.C. murders: expert

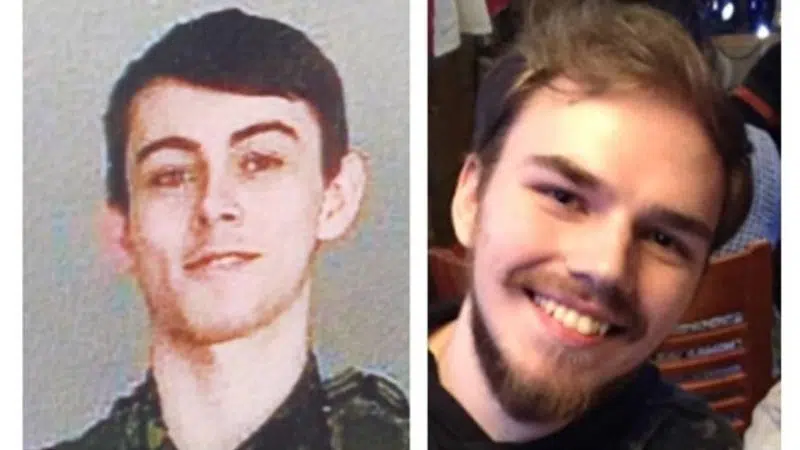

VANCOUVER — A criminal profiler says investigators should find clues about why two men might have killed three people in northern British Columbia and whether there was a leader and a follower.

Jim Van Allen, a former manager of the Ontario Provincial Police criminal profiling unit who has studied 835 homicides, said evidence can determine what happened in most cases. But it can be harder to determine motive, and that’s where behavioural analysts come in.

“The evidence is going to take them so far. It’s going to tell them who did what to whom, at what time and how. But it’s probably not going to answer the big question on everybody’s mind: ‘Why?'” he said.

“That’s one of those behavioural issues that has to be interpreted to some degree from people’s conduct, their behaviour during the crime, what was done to the victims” and other factors.