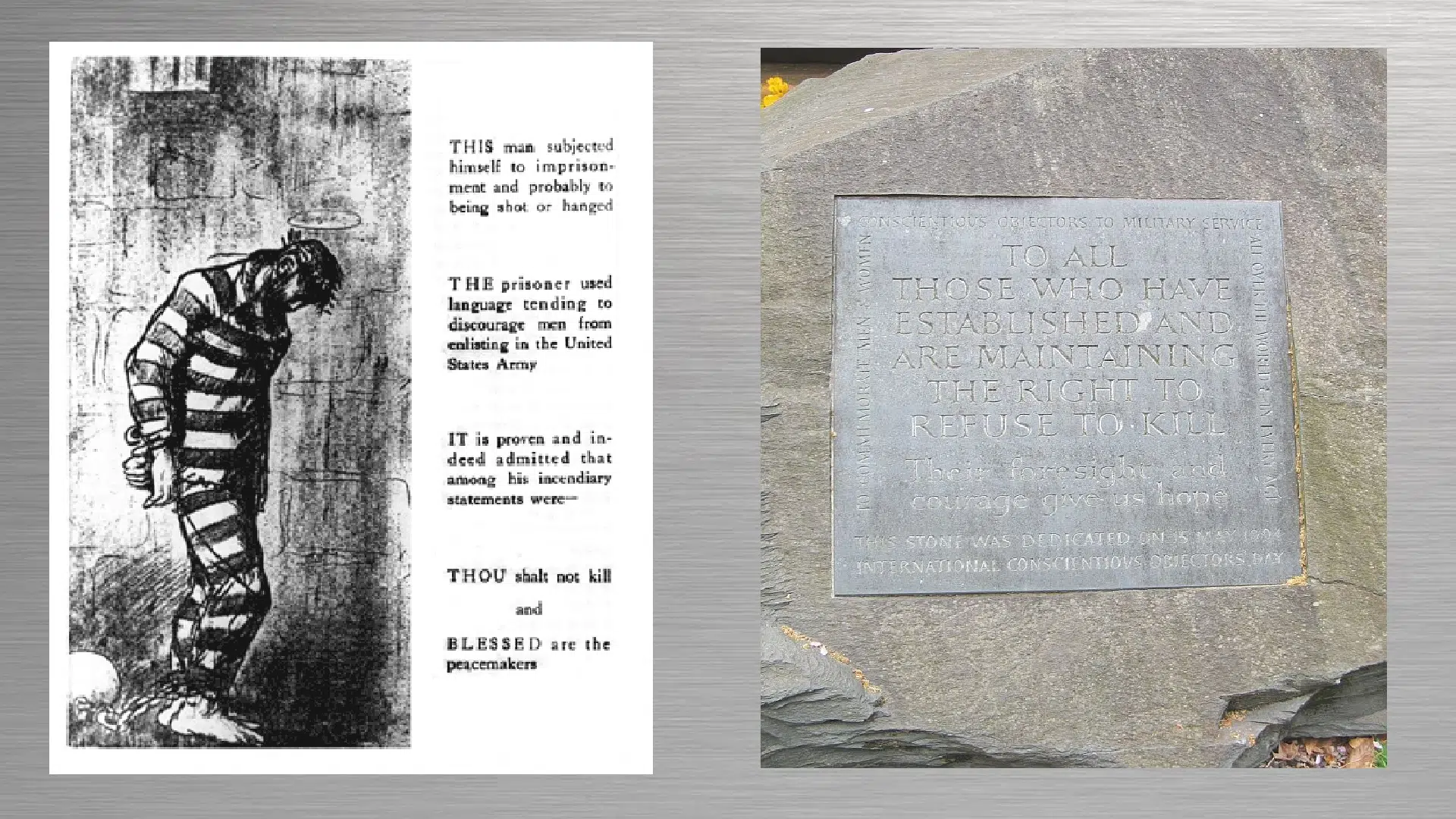

The other side of The Great War: Conscientious Objectors in Canada

LETHBRIDGE – “They were ridiculed as cowards. They were ridiculed for not being ‘manly enough,’ not following the masculine norms of the day.”

Dr. Amy Shaw is an associate professor of Canadian history at the University of Lethbridge, who has studied ‘Conscientious Objectors’ during the First World War.

“A good way to look at it, is to look at the people who didn’t quite fit in, and what people said about them and what they wanted them to do… Most of them were rebelling against something that the government wanted them to do. But they weren’t the kind of people generally, who would do that. They were people who followed the norms of society, who wanted to obey the laws. So, we have this situation where we have otherwise good citizens in this difficult situation.”

What is a ‘Conscientious Objector?’